It can move on its own just like a robot and kills microbes by simply shining a light, sometimes disinfecting an entire hospital room in just eight minutes. Some manufacturers call it a germ-zapping robot, and hospital staffs have even gone so far as to nickname their machines R2D2.

More than 50 companies now manufacture some form of ultraviolet (UV) technology disinfection machines, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress and investigates how the federal government spends taxpayer dollars.

So what exactly do these machines do? And how do they fit into an overall infection control program? We asked some manufacturers and a few infection control experts to weigh in on the newest high-tech machines sweeping the health care industry, make sense of the science and vast amounts of data, and help end users make an informed decision.

How Does It Work?

“UV technology works when a proper dose of UV light energy is emitted in the proper wavelength,” says Chuck Dunn, president and CEO of Tru-D Smart UVC, a UVC-technology product manufacturer. “And not all UV is germicidal efficient—meaning the process is capable of inactivating significant numbers of microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, and protozoa.”

In other words, says Lisa Sturm, MPH, CIC, director of infection prevention and epidemiology at the University of Michigan Health System, “UV light disrupts the cell wall—the casing around the bacteria—and blows it apart. Then the bacteria die.” She adds, “It’s pretty cool.”

Study up on UV Tech

A simple Google search will yield countless medical studies on the effectiveness of UV technology against microbes and health care-associated infections (HAIs). “As professionals are analyzing UV technologies, they need to look at the peer-reviewed literature supporting the device’s claims with regards to reducing infection rates at hospitals,” advises Daniel English, environmental services principal at Xenex Disinfection Services.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently conducted a multi-site randomized clinical trial, which concluded that a combination of manual cleaning and measured-dose UV light results in a 30-plus percent reduction of infections for patients who stay in rooms previously occupied by infected patients.

Dr. John McKinnell, assistant professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at The University of California, Los Angeles, advises that consumers should take studies funded by manufacturers with a grain of salt. However, he adds, “I characterize the data on UV technology as solid and scientifically sound, but there’s not one study that says you have to use this.”

McKinnell points to a few unbiased studies to help end users understand the technology’s position in current terms. First, he cites a landmark study from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), “The Role of the Surface in Health Care-Associated Infections,” which solidified the role of terminal room cleaning and the proper and thorough disinfection of all surfaces in the room in the battle against HAIs.

From there, McKinnell points to a study from June 2016 in the American Journal of Infection Control, “Influence of Pulsed-xenon Ultraviolet Light-based Environmental Disinfection on Surgical Site Infections,” which looked at surgical site infection rates, and takes the focus even further beyond HAIs into more specific types of infection rates.

Another study McKinnell prefers compared the use of UV technology with a hydrogen peroxide vapor, another popular mode of hospital disinfection. The study, entitled “Comparison of the Microbiological Efficacy of Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor and Ultraviolet Light Processes for Room Decontamination,” published in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, concluded that the UV technology needs a line of sight to be fully effective. “The key thing with UV light is that a light has to shine on the surface,” says McKinnell. “This study showed the hydrogen peroxide vapor was a little better for room decontamination and that’s largely because the UV light has to see what it’s decontaminating.”

Workloading and Production Rates

When it comes to disinfection, whether that’s in the operating room, a terminal room, or anywhere else in a hospital, cleaning is still absolutely paramount. “The most important message is that UV technology absolutely does not replace physical cleaning, [using] what we call elbow grease,” says Sturm. “The UV light can’t penetrate through bio-burden like blood and dry secretions. Anybody who thinks, ‘we don’t clean thoroughly in every nook and cranny but that’s ok because the UV light will pick up after us,’ is wrong.”

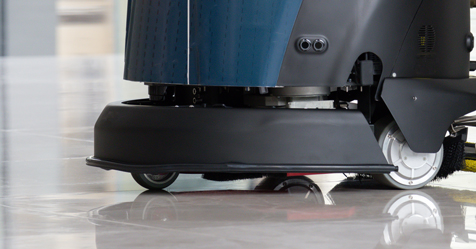

English explains what a typical process for a UV robot looks like as such: “Typically, the environmental services team (EVS) member will clean the patient bathroom, then run the robot in the bathroom while they are cleaning the rest of the room—removing trash, dirty bed linens, etc. When the room is visually clean, they will run the robot in two four-minute cycles—one cycle on each side of the bed— to make sure that all of the high-touch surfaces are exposed and disinfected.”

The length of time it takes UV technology to disinfect a room varies depending on the product. When the process is quick, it is easier for health care facilities to turn over rooms. For example, with the hydrogen peroxide vapor technology mentioned in the study, a room can be closed for an extended period of time while the technology sprays, because you need to seal off the ventilation before deploying the spray, and then you need to use a second machine to suck the vapor back out, according to Sturm, whose hospital system uses this process. “UV light is very simple to use,” she says. “You roll in and turn it on and then the minute the UV light is done, the room is ready to occupy almost immediately.”

This helps the business of the hospital by keeping rooms open and limiting isolation cases. There’s also a public relations boost from the allure associated with UV-robot technology.

Some of the robotic machines are able to move on their own, which frees up EVS workers to complete their tasks while the robot positions itself to disinfect based on pre-loaded software. The robots also communicate with staff through audio and text message alerts, cutting down on time and increasing production rates.

Advice for Investing in the Technology

“It’s a big investment,” says Sturm. These machines can cost up to US$80,000, and testing is an important step to make sure you are investing in the right technology for your needs. “You have to try them for a long time,” cautions Sturm. “Three months isn’t long enough. Six months will help you get good data.”

It may be difficult to get a free trial for that long, so you may want to rent the machine for an extended trial period. During your trial period, pick a goal and track your results. Your goal is likely going to be reduced HAIs, so make sure you connect your environmental services department with infection control and the purchasing department to come up with a testing plan and pay attention to your goal and your results.

“You want to pick units to test the machines on that are high-risk and have the most infections,” advises Sturm. “For us, that’s bone marrow transplant and burn units. It’s where you are going to see the heaviest, densest infection rates. Then you track.”

Training on the machines and their software are also two important factors to consider during trial and after purchase. (Editor’s note: See sidebar for a list of questions to consider when shopping for UV technology.)

The Future of UV

“There are 5,000-plus acute care hospitals in the United States, not including outpatient surgery centers, long-term acute care, and skilled nursing facilities,” says English. “Approximately 10 percent of the acute care facilities have adopted UV technology in the United States, so there is significant room for growth. And HAIs are a global problem, so the international market is important as well.”

Airlines are looking to use UV technology to self-clean lavatories, and those in the industry believe this technology can have a strong place in many other markets as well; it has been used to sterilize water in the food service industry for more than 50 years. Where it can go from here is anyone’s guess, but it certainly has a foothold in the health care environment.

“The UV disinfection market is expected to grow from $30 million in 2014 to $80 million in 2017,” says Dunn. “No-touch enhanced disinfection methods have become main stream in just the past few years.” One of the reasons for this, according to Dunn, is that hospitals face Medicare reimbursement cuts for the number of patients who are affected by a health care-associated infection or for readmissions.

Questions to ask your team and manufacturer if you are interested in investing in UV technology

- Has the technology been proven to reduce infections?

- Has that data been validated or gone through peer review, and who funded those studies?

- What sort of implementation and training does the vendor provide to ensure infection reduction success?

- Do we track for health care-associated infections? If not, can we start for the trial period?

- Which units will we use to track our outcomes? Which infections will we track?

- Who will use the machines (will EVS be trained or will the manufacturer operate the machines during the trial)?

- Can we afford to rent the machine for an extended trial period?

- How long does the machine take to disinfect the room, how will production rates benefit, and will isolation rates go down?