In a previous CMM article we introduced the concept of “cleaning aerobics.” This term warrants further clarification on how to use light reflections to sharpen a cleaning technician’s “eye for detail” and improve cleaning results.

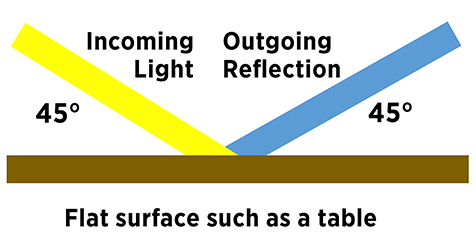

Not being a scientist, I looked up the elements regarding the optical law of reflection. The angle of light that strikes a surface is called the incident ray. The angle that is reflected from a hard surface is called the reflectant ray. Coincidentally, the angle of incident (incoming rays) is the same angle as the reflection rays (outgoing or bouncing off).

This means if overhead lights or outside lighting shines on a flat hard surface at a 45-degree angle, it is illuminated and viewed at a 45-degree angle from the opposite direction (Figure 1). The best way to view unnoticed soil is to catch light reflections that illuminate hard surfaces by following the angle of reflection.

Figure 1. Angle of reflection

Practice cleaning aerobics

Mastering the art of catching light reflections often requires bending of the knees; twisting of the hips, torso, and neck; and scanning with the eyes. The person who applies this aerobic process will typically deliver superior cleaning results compared to a person who does not. Of course, these results assume that the cleaning solution efficacy and tool operation is at maximum performance.

Let’s see if the proof is in the pudding. We cleaned a breakroom counter with an approved cleaner and a microfiber cloth, using proper agitation. We followed that up with a complete drying. Without coordinating our cleaning action by the aerobic twist, the law of reflection from this angle showed a perfectly clean surface (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Clean surface by observing from one angle

However, by moving to a different position (employing cleaning aerobics), the law of reflection displays a hardened soil that was not removed. I am not sure if it was dried pudding, but it fits in nicely with the scenario (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Law of reflection displays a hardened soil

Likely, it was a sticky food substance previously overlooked by cleaning staff. Practicing cleaning aerobics instills a higher level of thoroughness and attention to detail. In turn, this improves quality and reduces cross-contamination. Utilizing the process allows a cleaning technician to perform a surface pre-inspection to determine if a particular soil will require a specialized approach.

For example, if you are cleaning school desks and pick up the reflection of hardened glue, then you will need a plastic scraper in addition to a cloth. You know from experience that scrubbing with a cloth for 10 minutes will not budge the glue.

In another example, the final results after mopping a hospital patient room floor displayed skipped soil after the angle of reflectance was brought into the picture. The term “hospital clean” did not fit the scenario (Figure 4). Cleaning aerobics might have precluded this outcome.

Figure 4. Skipped soil on a hospital floor

Light reflections also display the disinfectant coverage applied to a surface and provide luminosity to signal if you need a heavier coat of cleaner. However, keep in mind that not every square inch of a flat surface can be observed with reflectant light.

Counterattack the soil

Modifications to the cleaning process can bring transformation. Cleaning crews can adjust the process to match soil loads whether they are light, medium, or heavy. They may also adjust the chemical and its strength for each cleaning task.

We know it’s counterproductive to use bowl cleaner for nightly window washing. Or, to use a window cleaner to remove heavy mineral buildup from a toilet. However, other factors also impact the cleaning results.

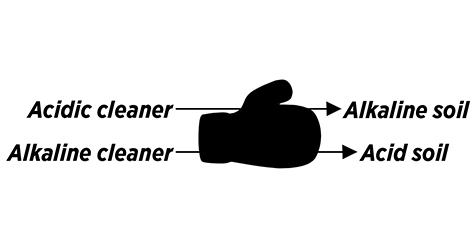

Typically, an alkaline soil such as mineral buildup is best removed using an acidic cleaner. Conversely, acidic food residue may be best removed using an alkaline cleaner (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Illustration of the conventional approach

X-ray vision (figuratively) is helpful when cleaning heavy soil. Train technicians to peer through a cleaning solution to observe and determine if the soil is budging. Unresponsive bonded soil signals the need to wipe the surface and apply a different cleaning product that is specifically formulated for the soil encountered.

Consider using a solvent-based product to remove adhesive. If the first application of the cleaning agent failed to remove the soil, perhaps use a scrub pad with the second application. Encourage staff to adapt to accommodate the nature of the soil. Then, challenge them to strive for excellent results in place of misguided effort.

Remove residual residue

Using the correct amount of cleaning product also can lead to better results. Too often we notice cleaning personnel applying too much cleaning mixture to a surface.

An excessive amount of solution will extend the wiping and drying process. Often, an employee will rush through the process and advance to the next area before the surface is sufficiently dried (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Dried-on cleaning agent

I hope these cleaning tips will prove helpful in your operations. Feel free to send me your feedback.